When I first started learning guitar, it seemed impossible. Here’s a short list of things I had to figure out starting from the very basics:

- Holding the guitar

- Proper posture

- Placing my fingers on the neck

- Holding a pick

- Fretting a note

- Plucking a note

- Fretting multiple notes

- The names of the strings

- The numbers of the strings

- How to play chords

- How to strum chords

- How to pick individual notes from chords

- How to sing while playing

And so on. Those first few years involved a lot of looking at the lesson in my guitar book, looking down at the neck, s l o w l y putting my fingers in the right place, and then plucking out a few notes that sounded all wrong. It seemed like none of it would ever fit together cohesively.

It wasn’t until a few years into playing that I realized I could do a lot of this stuff without thinking. I’m still no whiz on the guitar, but I can muddle my way through pretty convincingly (which is also how I do improv). What had happened was, I had stopped trying to be good at everything all the time. If I was practicing fretwork, I would focus on making sure I had clean and consistent tone. Rhythm fell by the wayside in favor of making the notes I was playing sound good. After a while, I was competent at most of it without thinking.

I still do this today. If I’m learning a new song, I focus on one area first–maybe I practice switching between chords with a very simple rhythm at a very slow pace, making sure I know where my fingers need to go next to keep progressing. Only then do I try figuring out a strumming pattern, or picking out individual notes. Eventually, a full song emerges from my fingertips.

Stop trying to have it all

Here’s the thing: you can’t be good at every part of improv all the time. You just can’t. Even your favorite improvisers fail to execute perfectly on every aspect of every scene. So, especially if you’re just starting out, cut yourself some slack. You don’t have the reps in your bones to do this stuff automatically yet. You’ll get there. You just have to trust that you will.

But what do you do in the meantime? Well–

You ever notice how, in a class or rehearsal, you do fine if you have one thing to focus on, but once you’re up on stage, you forget to do any of that? That’s because you’ve opened up the potential scenes you can do to as wide a range as possible. If you can do anything, you often forget to do something. What does that mean? I don’t know. It sounds good.

No, I do know. Here we go.

Don’t do anything. Do something instead.

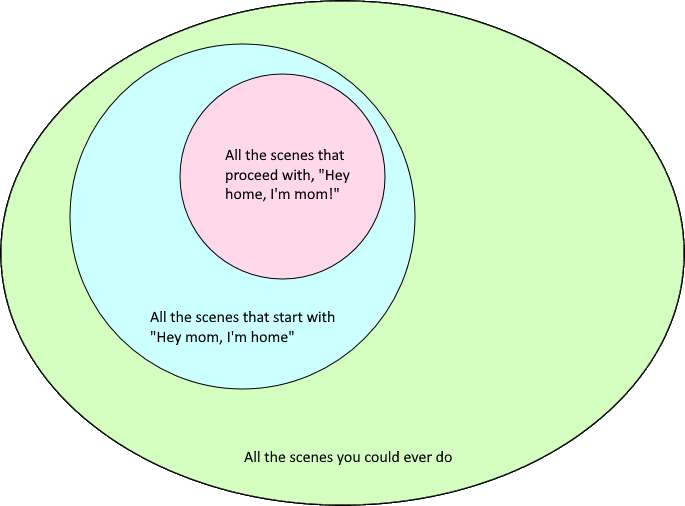

When you step on stage, you have infinite possibilities ahead of you. The moment someone says or does something, you reduce the potential scenes to a smaller infinity. You can still do anything, but the things you do will always follow what came before, so you’re in one possible reality. It’s like this bad diagram I just made:

Once you’re in the pink circle, you can’t jump back out again to the green one. You’re in that scene until it’s over. I’m so sorry.

The problem with having all this space to play is that there are tons of land mines, pitfalls, and booby traps waiting for you that all lead to the same place: the bad scenes. And, to quote a meme, when you fuck around, you find out. If you get up on stage and just try anything you are going to find yourself falling into one of these traps sooner or later. If you focus on something, you’re going to have a higher success rate. But what should you focus on? How about… something you learned in an improv class?

Here’s the thing: improv exercises are designed to make you better at improv. Shocking, I know. But it stands to reason that if it’s a good exercise, it should have a higher success rate than getting up on stage and doing whatever untrained monkey shit you want.

There’s a great exercise where one player enters with a mundane line of dialogue and the other player has a big emotional response to it. It reinforces a ton of awesome improv fundamentals, but you may also notice that many times if someone does that exercise in front of you the scene is usually pretty good. Sure, someone might walk through a table or forget a character’s name, but at least they’re watchable.

So here’s a trick you can do: just pick one thing you learned in a workshop or class earlier in the week that worked, and do that thing at every opportunity. I’m not saying do the same scenes, heaven forbid, but use the same techniques. Use them over and over again. And you might say, “hey, that’s stifling my creativity!”. But if you found out that using a particular bat made you more likely to hit home runs, would you be like, “forcing me to use that bat stifles my creativity” or would you be like “sweet, gimme that home run bat”?

Good improv exercises start you in a smaller circle in the diagram above, but one that is filled with a higher percentage of good scenes. Why are you afraid of just starting there? I promise your favorite improvisers all have tricks like this that they learned in classes just like you did. Ask them. They’ll tell you as much, if they’re not liars.

Eventually, you’ll do that thing enough that it becomes second nature. You’ll find that you no longer have to think about the chords, and you can focus on the strum patterns instead. And so on. Please complete the analogy for yourself because I kind of forgot about it until just now. Learning improv is like guitar–don’t fret. Wait, no, that’s terrible. If you didn’t fret a guitar it would sound awful. Forget the guitar stuff. Just, uh…

Do one thing good tonight. The rest will follow.

Maybe it’s voices. Maybe it’s point of view. Or maybe it’s emotion. Perhaps it’s just starting your scenes with love instead of mild annoyance. Get out on stage and tell yourself, “I’m going to be the best person at this one thing tonight”. Literally steal something that you learned in a workshop or a class or a rehearsal earlier in the week and just do that one thing the whole time. You might just find yourself doing a bunch of really good improv without thinking about it.

Or maybe you won’t. That’s improv, baby! Better luck next time.